Lose the Past, Lose the Present

by Dr. John C. Rao

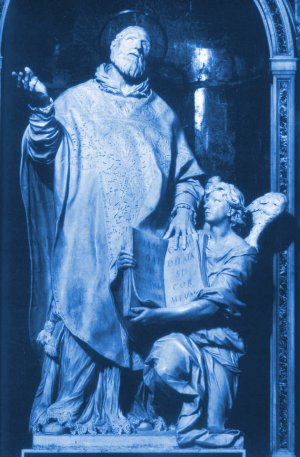

Alessandro Algardi, 'St Philip Neri' (1636-38)

Santa Maria Vallicella, Rome |

It is doubtful that many tradition-minded Catholics would question the argument that he who controls the depiction of the past also has a powerful means for controlling the present. After all, it seems quite clear that once the picture of historical events has been painted by those who have the will and the power to place their canvas before the whole population's eyes, it will be virtually certain that few people will critique the scene it offers. Indeed, it will be virtually certain that almost everyone will interpret current issues in the context of the sketch of history that has been made familiar to them.

Although they may not know this to be the case, believing Catholics are nevertheless often among the worst offenders in the neglect of history. And in neglecting it, they contribute to allowing their enemies uncontested opportunities for poisoning the attitude of millions of our contemporaries towards a religion whose true history might actually appeal to them.

Catholics began to lose control over the depiction of the past already at the time of the Renaissance. This was certainly not because of Humanism and Humanist methodology in and of themselves. Humanist love for language, literature and antiquity in general was valuable in the development of what is called "positive theology", a theology dedicated to exploration of the primary historical sources of Christian life: the Scriptures, the Fathers, liturgical texts, early canonical legislation, conciliar decrees, and references to the behavior of the faithful through the ages. It also became a powerful stimulus to the publication of broad texts in Church History, which sought to coordinate the information pouring in from those varied sources. The problem was that certain Humanists constructed out of their love for ancient rhetoric and antiquity an historical vendetta against what they saw to be a stylistically barren and barbaric medieval culture. "Systematic" or "speculative" theology, a theology that leaned heavily upon logic and other philosophical tools to build the grand cathedrals of Christian thought characteristic of medieval scholasticism, was among the prime targets of their barbs. The theme of the corrupted medieval world, guided by overblown and drably-expressed dogmatic visions lacking contact with real life, had been created. Such a theme could not help but stain the reputation of the Catholic Church, which had reached such high pinnacles over the centuries since late antiquity.

It was, however, the Reformation which really put the Catholics on the run, due to the persistent, enthusiastic, and often quite talented efforts of Protestants conversant with Humanist methodology to use this literary tool as a weapon in the anti-papist arsenal. Labeled innovators by their Catholic opponents, and yet convinced, as they were, that the Church had introduced changes of disastrous proportions into the life of Christians, such Protestants hammered at arguments drawn from positive theology to drive home their apologetic points. They knew how to uncover scriptural, patristic, legal and liturgical problems embarrassing to the Church. They knew how to weave these into broad historical assaults calling her whole mission into question. Their feel for language, now extended to the vernacular in addition to the ancient tongues, enabled them to present their accusations in gripping, often rude, but always crystal-clear ways to wide audiences. Hence, with a sense of purpose, science, and style, they fixed the theme of medieval Catholic corruption even more firmly in the minds of both the intellectual elite and the masses.

Martyrology was one field of study of Christian behavior that Protestants used to build an anti-Catholic world view from a very early date. What they did was to link up the suffering of Christian heroes from the past with those of "Gospel Christians" of their own day, so as to show that the persecution of true believers was a specialty of the Roman Church from time immemorial. Martyrologies of this type appeared in many languages. Prominent among them were Martin Luther's The Burning of Brother Henry in Dithmarschen (1525), William Tyndale's Examination of Thorpe and Oldcastle (1535), Ludwig Rabus' Stories of God's Martyrs (1552), Jean Crespin's The History of Martyrs (1554), Matthias Flacius Illyricus' Catalogue of Witnesses to the Truth (1556), Adriaen van Haemstede's History and Death of the Pious Martyrs (1559), both the Latin and English editions of John Foxe's Acts and Monuments (1559/1563), Agrippa d`Aubigne's poem, Les Tragiques (1580), and Simon Goulard's more ambitious History of the Reformed Churches of the Kingdom of France (1580).

A sub-category of this literature involved a specific attack on the Inquisition, especially useful in places where it was at first difficult outrightly to condemn the Roman Church, and where one might also tap into anti-Hapsburg and anti-Spanish sentiment. In this line were the anonymous On the Unchristian Tyrannical Inquisition that Persecutes Belief, Written from the Netherlands (1548), Francesco de'Enzinas' History of the State of the Low Countries and the Religion of Spain (1558), and A Discovery and Plaine Declaration of Sundry Subtell Practices of the Holy Inquisition (1567) by "Montanus" (Antonio del Correo), translated into English by Thomas Skinner (1568). Though not Protestant, the Venetian Servite Paolo Sarpi's On the Office of the Inquisition (1615/1638) was a further addition to the genre. It was out of these and related attacks that the famous "Black Legend" was born, through which figures like Philip II could be dehumanized, and people spared the (by definition) impossible task of finding serious reasons behind Catholic action in this realm.

Again, as some of the titles noted above demonstrate, Protestant efforts went beyond using and drawing conclusions from merely one field of study of Christian behavior in the assault on Catholicism. A complete anti-Catholic history had to be written, with respect to individual nations as well as with regard to the life of Christendom as a whole. Martin Luther and Jean Calvin were both involved in this sketching-out of the broad Romaphobic landscape, the former tracing the roots of Catholic error to an earlier date, the latter adding the Carolingian Family and its insatiable ambition to the list of villains responsible for the deviation of the Church from its proper constitution. But the most impressive Reformation-inspired Church history, because of the universal vision it offers, is the "orthodox" Lutheran work produced by Matthias Flacius Illyricus and his associates at the city of Magdeburg. This text is referred to as The Centuries (8 Vols., 1559-1574), its name clearly following its manner of dividing up the material presented. Here one finds many of those spicy, but erroneous stories, like that of Pope Joan, which still figure into the average "educated" man's anti-Catholic repertoire.

The painters of the anti-Catholic historical picture never slackened their efforts. Enlightenment thinkers of the eighteenth century entered into the studio following the Reformation Era to sharpen the image. By the 1800's, the "Whig Interpretation of History" (to borrow the title of Herbert Butterfield's famous book on the subject), which continues to batter Catholic self-esteem on the popular level, was complete in all its particulars. The world was given a black-and-white standard by means of which to judge all events, past and present, one which condemned anything Catholic in argument and culture as being by definition fantastic, alien to real life, retrograde, and drab to boot. Meanwhile, the same measure was used to show that everything that tore at the heart of Catholic Christendom (and, given the increasing role of Anglo-Saxon influence in undertaking this mission, all that aided the process of Anglicizing the globe) was progressive, intelligent, and good.

Some of the Council Fathers at Trent felt the sting of attack from Protestants using positive theology against the Church deeply. Time and time again, they had to admit that while they firmly believed Catholic doctrines to be true, and Catholic canonical norms and liturgical practices to be justified, they were frequently ignorant of where these came from and upon what they were based. Hence they felt themselves to be at a disadvantage in dealing with Protestant critiques of indulgences, communion under one kind, private confession and clerical celibacy as unjustifiable innovations, and explaining why people rejecting them should come under ecclesiastical censure. Repeatedly, help had to be sought from Catholic experts in positive theology outside the Council to save it from confusion and potential ridicule.

And fortunately, such Catholics there were, skilled in the use of the same tools as their Protestant opponents, but ready to turn them to the defense of the beleaguered Church. In the 1500's and 1600's, Catholics engaged in research on the primary sources of Christian teaching and life were legion. Scripture was being probed by men such as Sixtus of Siena (d. 1569) and Cornelius à Lapide (d. 1637); patrology by Cardinal Guglielmo Sirleto (d. 1585), Marguerin de la Bigne (d. 1589), Fronton du Duc (d. 1624), and Luc D'Achery (d. 1685); dogmatic history by Dionysius Petavius (d. 1652), archeology and martyrology by Onofrio Panvinio (d. 1564) and Antonio Bosio (d. 1629), author of Roma sotterranea. Guides to Christian literature in general, following in the line of St. Jerome's early work, were provided by Suffridius Peti (d. 1597), Antonio Possevino (d. 1611), Angelus Rocca (d. 1620), Cardinal Roberto Bellarmine (d. 1621), and Miraeus (d. 1640). The lives of the saints were studied by Laurentius Surius (d. 1578), Heribert Rosweyde (d. 1629), John van Bolland (d. 1665), and the Bollandists, as well as (among their manifold pioneering endeavors) by the Benedictine Congregation of St. Maur, or Maurists, and its perhaps most famous representative, Jean Mabillon (d. 1707). Cardinal Pietro Sforza Pallavicino (d. 1667) dedicated his labors to analysis of the recent contributions to positive theology from the documents and events of the Council of Trent.

More than this, broad historical texts constructed from primary source materials and capable of answering the Magdeburg Centuries were also being produced. The name that immediately rises in this context is that of Cardinal Cesare Baronius (d. 1607), author of the Annales ecclesiastici (12 Vols., 1588-1607).

Baronius' story is linked with that of St. Philip Neri (d. 1595), founder of the Roman Oratory. Neri was fascinated by the direct approach to the ancient martyrs and the various sites of Christian antiquity which was possible in a city like Rome; hence, his popularization of pilgrimages to the catacombs and early basilicas and stational churches. Aware as he was of the Magdeburg Centuries, and the way in which Protestants were trying to claim for themselves the role of representatives of a Christian antiquity subverted by Catholic Rome, Neri promoted an historical response to their threat. He urged--indeed, commanded--Baronius, who had moved in his orbit from a very early age, to prepare lectures on history for the meeting of his Oratory from 1558 onwards. From such modest beginnings, his work expanded, continuing even after he became a cardinal in 1596. He eventually completed twelve volumes on Church history, carrying the Annales down to the eve of Innocent III's reign in 1198. Baronius, in consequence, made the Catholic view something that had to be answered rather than just an inviting target for any hostile scholar's sharpshooting practice.

A number of nations offered men who sought to follow in Baronius' footsteps in the 1600's, including the Italian Oratorian, Odorico Raynaldi (d. 1671). Still, it was France, so important to Catholic thought and life in every regard throughout the seventeenth century, that perhaps did the most in this realm. French scholars laboring in varied fields of positive theology in the 1600's turned their attention at one time or another towards the publication of broad ecclesiastical histories. Perhaps not surprisingly, it was a member of the French Oratory, Charles Lecointe (1611-1681), who is most noted for such work. Eight volumes of his Annales ecclesiastici francorum appeared between 1665 and 1683.

In short, a bright future for Catholic historical studies, drawing from original research in positive theology, might have seemed secured. The chance for Catholics to shape the world's attitude toward the past, and thereby gain the edge for interpreting the present, might have been judged very good indeed. Unfortunately, despite the massive efforts of still later heirs of Baronius, including the rather recent figures of Ludwig von Pastor and Hubert Jedin, this desirable Catholic shaping of historical attitudes never materialized. It was the Humanist-Protestant-Enlightenment-Anglo-Saxon-Whig presentation of the past that was to tighten an iron grip on the western mind, putting the Catholic perpetually on the defensive, incapable of organizing the framework of scholarly debate, fighting merely to be heard, much less harkened to.

The explanation of what went wrong is a subject worthy of an entire volume, and not just a paragraph or two in a short essay. Nevertheless, certain Catholic contributions to this debacle should be noted here.

On the one hand, although intensive work in positive theology continued throughout the eighteenth century, some of the Catholics engaged in it fell prey to that contempt of traditional systematic and speculative theology originally inspired by certain Humanists. Indeed, this tendency was already noticeable in the 1600's as well. Yet without a systematic Catholic theology to complement it, positive theology yielded nothing but raw data which still had to be guided by an organizing principle to make it fruitful. The organizing principle came from the zeitgeist, the "spirit of the times", a power that is difficult to resist at any moment and in any land. And the zeitgeist, by the 1700's, had its own systematic cosmology, a hodge-podge of contradictory literary, heretical, mathematical, and scientific dogmas, hammered at by an enthusiastic army of writers who promoted it as the latest progressive element in the historical picture described above. Hence, the results of specific Catholic research were often fit into the system of the enemy, by now taken as a given, as the obvious Diktat of "common sense". Creation of a distinct general Catholic vision of history was rendered superfluous and downright unthinkable. Catholics could work, but their enemies would tell them how their work could be used and what it meant.

On the other hand, Catholics concerned for the presentation of a general picture of history from an orthodox viewpoint, simultaneously drawing from positive theology and yet aware of the need to operate under the guidance of systematic theology, were not given the full support that the importance of their work deserved. It is not surprising that even in the seventeenth century, the fifth Jesuit General, Claudio Aquaviva, found it impossible to carry to completion plans for a Catholic Academy of History. The Church was in the commanding position at the beginning of the growth of the anti-Catholic historical theme. She was all too frequently as indifferent to making massive new intellectual efforts to oppose those whom she considered to be simple rebels as she had been to undertaking serious purgation of the scandals that helped to feed the Protestant Reformation. Having built up a systematic theology which, together with the ancient philosophical heritage, worked impressively to defend belief both in an ordered universe and its need for redemption, Catholics did not necessarily see why one had to undertake a complementary study of the roots and development of the Christian message. Moreover, historical research could cause painful political conflict, as Baronius discovered in his battles with Spain over Hapsburg claims to special, age-old rights to control Church affairs in Sicily and Naples. Finally, digesting the fact that the victorious historical picture has been drawn to their disadvantage, and that much of positive theology's raw data has been dragged into a systematic attack upon the Church, many Catholics have drawn the conclusion that history, its sources, and its tools must be rejected as innately suspect.

This brings us back to the initial premise of the article: the neglect of history by believing Catholics. In their love for the Church's Magisterium and just estimation of the superiority of systematic theology and philosophy in the teaching of Catholic truth, the faithful have indeed all too often exiled history from their midst as either unnecessary or misleading. Again, in their recognition of the faithless way in which the raw data of positive theology is frequently treated, they are tempted to avert their eyes from all primary sources and the historian's efforts to evaluate them. Why bother to study the "grammar" of the history of dogma in the work of the Fathers, they have, in effect, argued, when superior dogmatic treatises are available in the great systems of the medieval scholastics? Why look at eucharistic worship throughout the ages, they seem to say, when it might create the impression that the doctrine of the Real Presence emerged from history rather than having been taught outrightly by Christ?

These are not unreasonable questions, but they are queries which ought to be answered with a still firmer affirmation of the importance of historical work and all the disciplines of positive theology that feed it. The Catholic needs to know his roots if for pastoral reasons alone. Why? Because his abandonment of history does not free him from the personal problem of escaping the modern zeitgeist. In fact, it merely delivers him over to its control more fully. For in ignoring history himself, he allows the anti-Catholic picture of the past to reign unimpeded and shape all of his understanding of the environment in which he lives. Thus one frequently sees conservative Catholics using anti-intellectual arguments, and basing a defense of their positions on eighteenth century "Common Sense" principles, or, barring that, on nineteenth century notions regarding the respect owed to the will of the "Silent Majority". A deeper historical knowledge would demonstrate these concepts have been produced by opponents of Catholicism, and accord badly with basic Catholic beliefs.

Ironically, neglect of history hands one over more fully to the control of precisely that view of the past that condemns the meaningfulness of systematic, speculative theology itself! Moreover, rejection of positive theology and its raw data demonstrating the development of doctrine is not a sure barricade against disbelief. It buries a fount of evidence that the perceptive believer steeped in the practices of his religion can readily see to be of central value to apologetics. It then often replaces this solid testimony either with "proofs" from pious legends that strangely merge together with millenarian, apocalyptic or Americanist presuppositions, or with arguments which really amount to nothing more than stronger assertions of belief; the latter, as telling in their effect as the efforts of a passport controller speaking English louder and more deliberately to a foreigner who does not have a clue as to what he is saying, whether uttered in a whisper or a screech. In both cases, it is easy for opponents to demonstrate the same point with telling effect: that we do not know the historical foundations of what we claim to be an historical religion.

The mind of man was created by God to give us the means by which to try to understand nature and aid us in our approach to Him. Catholics do not have to fear it. That is why systematic, speculative theology which uses the mind to understand and explain the teachings of the Catholic Faith is a necessity and a blessing. But Catholics have nothing to fear from enriching their knowledge of the scriptural, patristic, archeological, exegetical, and general historical realm--of positive theology--either. For it is from such a realm that the food for speculation began. It is through regular contact with this realm that the systematic theologian reconfirms his conviction that he is not merely speculating in thin air, and gains a better understanding of how to become a great apologist.

How glorious it would be for the contemporary Traditionalist Movement to deepen its own knowledge of positive theology, and of broad Church History in particular. In doing so, it would see that there is very fine work being done in this sphere by many non-Catholic writers who might be won for the Faith by traditionalist efforts. And by deepening its knowledge in conjunction with a more profound practice of Catholicism, it would be in a position to forge a union of positive theology with the higher science of systematic, speculative theology more solid than that existing before the current crisis. Through this more perfect union, the Traditionalist Movement might begin the process of regaining control of the depiction of the past and the strength necessary, in consequence, to conquer the present.

Further Reading: